In marketing, it’s the brander who hurts instead of the brandee.

There are hundreds of definitions for branding. There are even dozens of good ones. For the moment, let’s think about this one:

Branding is the process of making one company’s products distinct from similar products offered by competitive companies.

Sure, it’s overly simplistic but let’s go with it for now.

Just as there are hundreds of definitions for branding, there are hundreds of ways to make one product distinct from another. We can invent distinctive, new features and functions, create distinctive, new ways to benefit customers, find distinctive, new ways to communicate about features and benefits (even if those features and benefits are not especially distinctive and new). And we can imbue our products with distinctive, intangible qualities that some people will find enticing.

Note that I said some people. But not all people. The process of making a product distinctive requires us to define exactly who we’re going to try to entice and exactly who we’re going to risk ignoring, or maybe even turning off.

And that’s why branding – real branding – hurts.

“But, I don’t want to turn my back on potential customers”

Having the guts to walk away from something is just as important as having the fortitude to embrace something. That’s hard to do because “I don’t want to turn my back on potential customers.”

But, think about it this way; what if you could be reasonably sure that the “customers” you’re walking away from would never really be your customers anyway? What if you could know that they’re so in thrall to your competitors that spending one more dollar on them would be foolish? And what if you could focus all your attention on the people who are most likely to find your offer appealing?*

Would Eastern Bank’s new “Join Us For Good” ad campaign succeed in rural parts of my home state of Alabama? Maybe not. But it doesn’t have to.

Bank of America is a 900-pound silverback of a brand. Bank of America can afford to be all things to all people. Or it can afford to try.

Eastern Bank, based here in Boston, MA, cannot, so they’ve made the conscious decision to be “the socially responsible, activist bank” (these are my words, based on their marketing materials, not theirs, so don’t come after me, Eastern folks, I’m a big fan) and to aim their offering squarely at people who will find that proposition enticing.

Despite not having the heft of a B of A, with 100 branch offices and almost $11 billion in assets, Eastern is not some hip, little boutique institution. So, to my way of thinking, it took a fair amount of fortitude to commit to a strategy and a message that’s absolutely guaranteed to hack some people off. You can follow a link at the end of this article and read how well Eastern is doing with this strategy. I wouldn’t have used them as an example if their results weren’t pretty remarkable.

Cannibals need love too

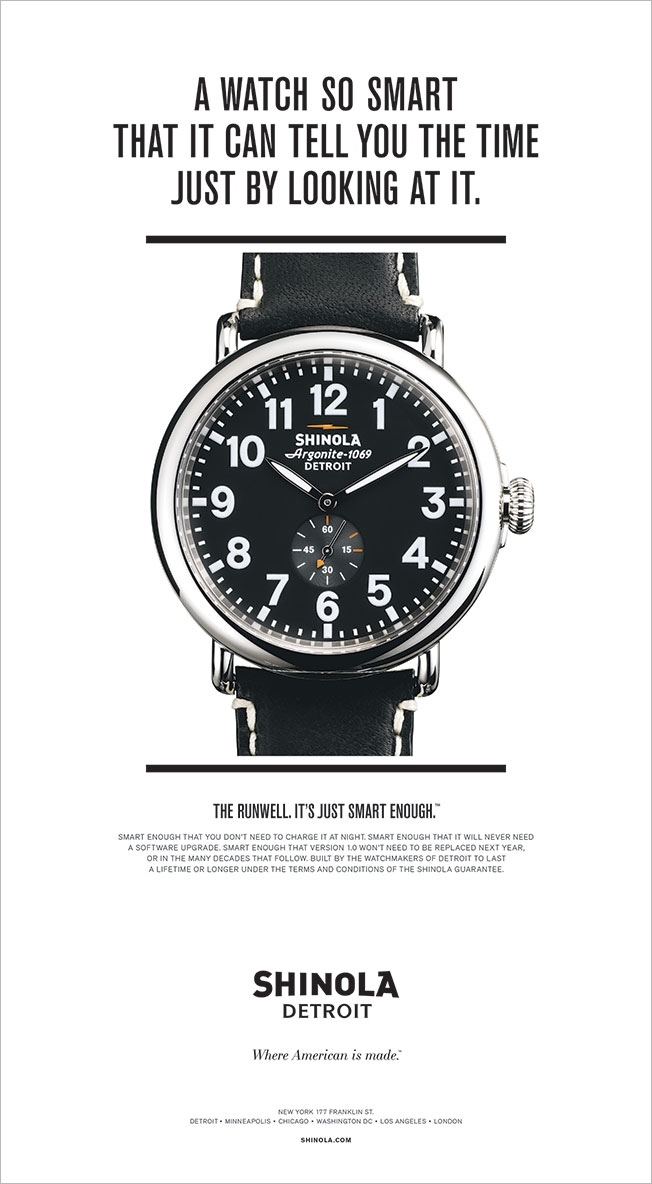

From the top, a 1980 Buick Riviera, Oldsmobile Toronado and Cadillac Eldorado. I think. Distinctive, huh?

If you’re a company with a portfolio of multiple brands, sometimes real branding means letting one of your brands take share from another. Big, multi-brand corporations can afford to take the attitude “If anybody is going to steal our business, it’s going to be us.”

Procter & Gamble and Campbell’s Soup are great at this and they’re thriving. Back when you couldn’t distinguish a Cadillac from a Buick from an Oldsmobile at twenty paces, General Motors was lousy at portfolio management, but they’ve gotten a whole lot better in recent years.

But, even for marketers who are good at it, going full-on Darwinian on your own brands is painful. For a CMO, it requires a clear vision, an iron will and the ability to turn a deaf ear to the indignation of the brand managers who are getting cannibalized by their colleagues down the hall.

John Mellencamp, marketing strategist

When you do it right, branding hurts.

Sometimes it means walking away from what seem like potential sales.

Sometimes it means allowing one of your brands to encroach on another, and may the best brand win.

But if the real goal of branding is to make what you’re selling distinct from similar offerings from competitors (and, let’s all be really honest, there are a lot of similar offerings available in almost every product category) then the hard choices have to be made by people who are comfortable with discomfort.

Next time you’re facing one of those hard choices, hum a few bars of Hurts So Good. Maybe that will make it easier.

But it probably won’t.

Linkography

- This post was inspired by my good friend and client, Phil Jones of AGCO Corporation. Thanks, Mr. Jones.

- *Exactly how to go about doing this will have to be the subject of a future blog entry. Short answer: call Motiv at 617.388.6749.

- Watch Eastern Bank’s new, flagship commercial and read up on their booming business (from The Boston Globe). I’ll bet that the folks at Eastern Bank don’t see Join Us For Good as a strategy so much as A Way Of Being. A Mission. A Raison d’être. And that beats a wimpy old strategy any time.

- In case you need to be reminded, here’s John Cougar or Whatever Mellencamp’s Hurts So Good video from a time when those cars pictured above were serious objects of desire. Sort of.